Developing a Setup

Dialing

it in

Finding

the balance

Once the car's basic parameters

are laid down, the next step is to balance it so that it's neither

understeering nor oversteering

too much. We want the car to be stable in corner entry, reasonably

neutral in midcorner, and to deliver the power progressively as

we leave the corner.

The primary parameters for setting

the car's overall balance are the anti-roll bar settings. Camber,

toe, and spring rates also can impact the car's balance, and the

damper settings (which we'll get to in a moment) can also impact

the car's balance in transient conditions and over bumpy surfaces.

The brake bias affects the balance in the entry phase of the corner

if the driver is trail braking.

At this point, we'll focus on

the anti-roll bars and brake bias. The rule of thumb for the bars

is stiffer at the front and/or softer at

the rear increases understeer, while softer at

the front and/or stiffer at the rear increases

oversteer.

When adjusting the bars, keep

in mind that changing the overall roll resistance (for example,

softening the front bar while leaving the rear the same) will

impact the tire temperatures and thus may require a camber change.

Also, going softer overall may allow the suspension to bottom

where it didn't with higher overall roll resistance, while going

stiffer overall may make the car more nervous over bumps.

For this reason, GRE incorporates

a feature which assists the user by optionally keeping the overall

roll resistance the same whenever the bars are adjusted.

For the brakes, more bias

to the front increases understeer, to the rear

increases oversteer and makes the car less stable in corner

entry. The trick is to find the most rearward brake bias the driver

can handle (given his/her style of corner entry) without destabilizing

the car, since this will shorten braking distances.

Anti-roll bar settings are impacted

by relative tire width. I believe GPL's cars all have the same

width tires at the front, and the same width at the rear. However,

the GP Lotus has wider rear rims, which makes its

rear tires more efficient. The GP Lotus seems to need higher

rear roll stiffness relative to the front than the other cars

to avoid having too much understeer.

Overall chassis width vs. center

of gravity height has an impact on the amount that the chassis

rolls. Wide chassis like the Ferrari and Lotus need a little

less overall roll resistance, while the narrow Brabham

and the BRM, with its second crankshaft way up high, need stiffer

bars.

Brake bias settings are a function

of the weight distribution of the chassis. A chassis with more

weight on the rear wheels at rest will have more

weight on them under braking, so it can tolerate more rearward

brake bias.

Brake bias is also a function

of the length of the chassis. In a shorter chassis, the

more weight is transferred to the front wheels under braking,

so the brake bias has to be set more to the front to avoid

locking the rear wheels.

Both anti-roll bar settings

and brake bias are impacted by the ride height. As you raise

the ride height, more weight is transferred, so bias needs to

move toward the front and the bars need to get stiffer

overall.

Road and Street Circuits

For most of the cars other than

the GP Lotus and BRM, I tend to start the bars at about 150

to 180 at the front and around 110 to 130 at

the rear. The GP Lotus starts out with nearly equal values

front and rear, in the 140 to 160 range. (Note that the Lotus

Trainers seem to lack the GP Lotus' wide rear rims, so they use

values similar to the other Trainers.) The BRM gets higher overall

values because of its high CG.

For brake bias, I'll start out

around 58 and move it back until the car gets unstable

under braking. Circuits like Rouen and Mexico, which have corners

where heavy braking while turning is required, will wind up with

a click or two more front bias to help me keep from losing it

in these corners.

I adjust the bars, keeping the

overall roll stiffness the same, until the car is comfortable

for me in the corners. If the outside edges of the left side tires

are more than a degree or two higher than the inside edges, I'll

go a little stiffer overall.

Ovals

Because of the right front tire's

tendency to overheat, I tend to run the rear bar fairly

stiff. Before GRE became available, with its extended

ranges, I always ran the rear bar at 200 at all but the flattest

of the ovals. Now I can experiment with even higher values. I

run the front bar much softer than the rear, especially

on the more steeply banked tracks.

Overall roll resistance starts

at road course values for the shallow ovals and goes up for the

steeper ones.

Brake bias is set the same way

as on road courses. On the fast ovals, it's easy to neglect brake

bias, figuring it isn't important since you don't brake in the

corners. However, you do need the brakes when things start to

go wrong ahead of you, so it's worth it to get a decent balance

on the brake bias.

Transient

responses

The dampers can be used for

tuning the car's transient responses.

Deceleration

Under lift throttle, braking

and turn-in conditions, going stiffer in bump

at the front will tend to promote more understeer,

as will going softer in droop, or rebound, at the

rear.

Going softer in bump

at the front and/or stiffer in rebound at

the rear will tend to make turn-in crisper; it will

make the car less stable under lift throttle, braking and

turn-in.

The dampers at the outside

front and inside rear corners will have more effect

on deceleration, since that is where the greatest suspension movement

will be.

Acceleration

Under acceleration, going stiffer

in bump at the rear and/or softer in rebound

at the front will make the car make the car tend to be

more reactive to throttle; it will tend a bit more towards

power oversteer, especially if the driver gets on the throttle

abruptly. Going softer in bump at the rear

and/or stiffer in rebound at the front will

soften the car's responses to throttle application.

The dampers at the inside

front and outside rear corners will have more effect

during acceleration.

Tradeoffs

Within reason you can trade

off anti-roll bar stiffness for damper stiffness. For example,

you can stiffen the rear dampers in bump and rebound, and soften

the rear anti-roll bar. This will make the car more responsive

to brake and throttle applications. It will also react more to

bumps at the rear.

An advantage of this is that

if the car gets into a big slide, it will be more likely to recover

itself. On the downside, the car will tend to understeer in long

corners. The net effect will be that the car will be more forgiving

but may be a bit slower, especially on circuits with long corners.

See the Damper

section of the Basic Settings

chapter for more details on the impact of changes in damper settings

on the car's overall behavior. See the Damper

Tables for a handy reference to which corners have most effect

on transient responses.

Gear

ratios

Barring a really bad setup,

most setup parameters don't have a huge impact on overall lap

times. As Dave Kaemmer says, most setups in GPL mostly impact

driver comfort.

However, gearing in GPL is critical,

particularly at tracks with a long, uphill straight. Spa, Kyalami,

and Elkhart Lake are examples of circuits where gearing can have

a significant impact on lap times.

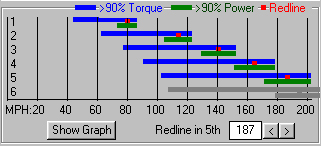

For

this reason, GRE provides a graphical aid (example shown at right)

for developing gear ratios. This graph has dots showing the speed

the car will be going at redline in each gear, and has bands covering

90% power and 90% torque. Once the top gear is known, this graph

helps the engineer to quickly select the proper gear spacing.

For

this reason, GRE provides a graphical aid (example shown at right)

for developing gear ratios. This graph has dots showing the speed

the car will be going at redline in each gear, and has bands covering

90% power and 90% torque. Once the top gear is known, this graph

helps the engineer to quickly select the proper gear spacing.

Top Gear

When developing gear ratios

for a given circuit, the top gear dictates the rest of the gearbox

setttings, so you need to get fairly close to the right top gear

first.

In Pro Damage mode, most of

the engines will not tolerate running at or above redline for

sustained periods. Even in Intermediate and Novice mode, abusing

the engine will lead to random blowups.

Therefore, it's important to

use a top gear tall enough

that the car does not quite reach redline on the longest straight.

This is particularly important on fast ovals and at road courses

with long straights, such as Spa, Monza, and Elkhart Lake. At

such tracks, the engine may go several hundred RPM higher in the

draft than when the car is running

alone.

I have a suspicion that the

Trainer engines may run out of steam even before their redlines.

They have relatively fat power curves, and it's possible that

their breathing is so restricted that their power drops off before

reaching redline. If that's true, it may be beneficial to gear

them so they never reach redline, and also to short shift when

going up through the gears. With the Advanced Trainer, even when

I think I've got a good top gear, I find that often I can go taller

and the car will go faster.

Low Gears

On the track, ideally the engine

will have just enough power to induce wheelspin in the lower gears

at full throttle. I think many people run the lower gears too

short. They like the responsiveness

of the car in the lower gears, and it's fun controlling wheelspin

with the throttle.

However, power above that which

can spin the wheels is wasted. It's much better to gear the car

so that this power is used at higher speeds. Therefore, I try

to pick the tallest bottom gears the car will pull in the lower

gears without bogging. I figure if the rear tires are just

on the edge of starting to spin under full power coming out

of slow corners, I've got the bottom gears just about right.

However, the available ratios

for the bottom two gears sometimes will not permit us to choose

as tall a gear as we'd like. The Cosworth, Repco, and both Trainer

engines would benefit from taller first and second gears on long

circuits, but unfortunately we have to work with what we've got.

Also, some engines have very

little torque in the low end of the rev range. The Murasama and

especially the BRM have this problem. Be careful not to gear these

so tall that they bog down coming off the slow corners.

Note that the Repco engine has

such a broad torque band that it's beneficial to use very tall

bottom gears. However, with a very tall first gear, sometimes

the Brabham won't start rolling even at full throttle from a dead

stop, if the engine is idling when you open the throttle. In this

case, a quick tap of the clutch will get the revs up and the car

will light up the tires and take off.

Gear Spacing

The obvious approach to gear

ratio spacing is to space the ratios evenly so that the redline

dots make a nice straight line from first to 5th. This approach,

however, would be wrong.

The car accelerates most quickly

in the lower gears, so it spends relatively little time in these

gears. The more powerful cars have an excess of power in the lower

gears as well. Any power above that which induces wheelspin.

On the other hand, the car spends

a lot of time in 4th and 5th gears on long straights. It's accelerating

slowly because most of its power is consumed by overcoming wind

resistence.

It's important to gear the car

so that most of the power and torque are

used where they are needed, which is at higher speeds.

Therefore, the most efficient gearing will show a parabolic

curve of the redline dots, with the high

gear dots spaced more closely together and the low

gear dots spaced farther apart. The broader an engine's

torque band, the closer together its top gear dots should be.

Spacing the lower gears out

and making the upper gears close together will also mean less

shifting in the slower bits, which will also save a little time.

Again there's an exception.

The BRM has such a narrow power band that it's not always practical

to space the gears as you would for the other engines. If the

low gears are spaced too widely, the engine bogs down after upshifts.

On circuits with long straights, optimal acceleration seems to

come from spacing the BRM's gears so that the redline dots are

just about in a straight line.

Sometimes it's beneficial to

set a certain gear a little taller or shorter than the setting

dictated by a smooth parabolic curve, in order to have just the

right gear for a critical section of the circuit. For example,

Kyalami has several short straights between second gear corners.

Some engines, with wide power bands such as the Ferrari, can be

geared so that no upshift to third is necessary.

Once you've optimized the lower

gears and the gear spacing, you may find that the car is accelerating

more quickly on the long straights, so you may need to raise the

top gear because now the car is reaching redline in top gear.

This, of course, may require you to readjust all the lower gears

to keep the optimal spacing.

Fine tuning

Keep in mind that many of the

setup parameters have an impact on the car's behavior that may

require adjustments to other parameters.

Once you've finalized your spring

rates and relative front/rear roll stiffness, you may want to

take a look at tire temperatures again, with an eye to making

a small camber change or change in the overall roll stiffness

to get the inside and outside edge tire temps on the left side

tire to be even. You may also want to see if the car will tolerate

a bit more rear brake bias, especially if you've done things to

increase the car's stability under braking and turn-in.

Once you're happy with the car,

you might try lowering the ride height a quarter of an inch. If

it still doesn't bottom the suspension

anywhere, leave it there. But check the tire temps again; now

you may be able to reduce the overall roll stiffness and go a

click farther to the rear on brake bias.

The whole process will be an

iterative one. As you hone in on a good setup, you'll probably

find yourself making smaller and smaller changes until finally

you've got a setup that's both comfortable and quick.

Your stopwatch and the seat

of your pants will tell the tale ... and that delicious feeling

in your gut when you realize you've put together a real sweetheart

of a setup.

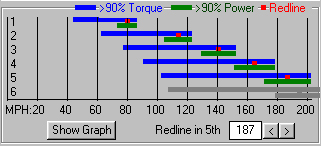

For

this reason, GRE provides a graphical aid (example shown at right)

for developing gear ratios. This graph has dots showing the speed

the car will be going at redline in each gear, and has bands covering

90% power and 90% torque. Once the top gear is known, this graph

helps the engineer to quickly select the proper gear spacing.

For

this reason, GRE provides a graphical aid (example shown at right)

for developing gear ratios. This graph has dots showing the speed

the car will be going at redline in each gear, and has bands covering

90% power and 90% torque. Once the top gear is known, this graph

helps the engineer to quickly select the proper gear spacing.